Anyone who’s been a participant or spectator in a conversation about racism in America knows that, as soon as the topic is broached, things usually become really difficult really quickly.

Difficult as in agonizing and antagonistic, awkward and awful.

In fact, at times it can be so difficult that one would be forgiven for wondering if there is any meaningful exchange happening. Until finally agreement is reached: let’s stop talking about this, like right now.

Why are these discussions so difficult? Why do they often feel so contentious and unproductive?

I’ve been wrestling a lot with that question, and I’m not really sure my current “answers” are that great, but here are some possibilities, stated rather briefly and quite boorishly. Some are perhaps all too obvious, others unproven, and still others tellingly absent–so, reader, please, fill me in. Here are my benighted thoughts–feel free to comment or critique:

1. A past that isn’t past: Routinely described as America’s “original sin,” for many today the monstrous abomination of slavery and segregation has forever established racism as the indelible and cataclysmic transgression of our nation. Discussing racism thus strikes a raw nerve and conjures up a past that we can (or should) never get past, a past that is itself (especially of late) contested, as exemplified in the NYT‘s disputed 1619 project.

And even to the extent that agreement is achieved in how to tell the tragedies of slavery and segregation, still further disagreement bursts forth: to what extent are these horrendous structural injustices still felt today? And should those injustices be addressed and remedied and, if so, how?

In short, the past is always haunting our present discussions, and if there’s one thing that’s tragically true about Americans, it’s this: far too many of us know next to nothing about our history.

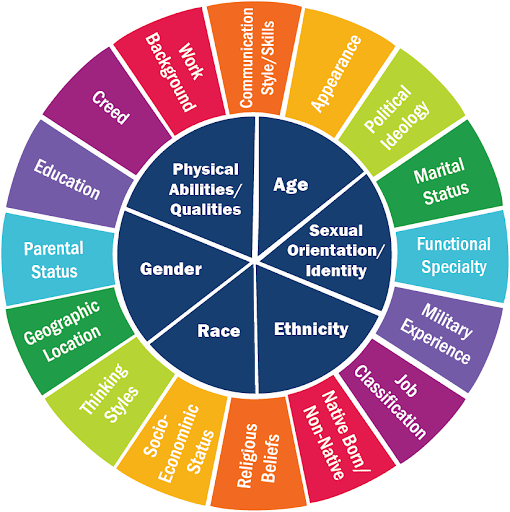

2. Overwhelming complexity: Not least because of its pernicious and pervasive character, racism is able to permeate practically every aspect of life. As such, to investigate its impact (whether actual or alleged) demands that we pursue a daunting degree of knowledge of, e.g., history, economics, statistics, health care, law enforcement and the criminal justice system, education, voting, real estate and mortgage lending, public transportation, gentrification and urbanization, finance and banking, constitutional law, and so on. Further, a number of concepts that are absolutely fundamental to understanding race and racism are simply not the easiest to grasp. Here are just two examples, one lexical, the other statistical:

– the difference between “ethnicity” and “race”: these two terms are regularly–and wrongly–used interchangeably, in both popular discourse and public documentation (e.g., a survey or patient information form): tersely and inadequately stated, while ethnicity has to do with lineage, race has to do primarily with looks (again, let me say: this is simplistic). As concepts, whereas the former is a legitimate and lovely aspect of human identity, the latter is a perverse fiction, which accounts for its ever-elusive character (e.g., who “counts” as a “white” or “black” person and why, and who gets to decide that? For a first-rate discussion of this, go here).

– a disparity is NOT proof of discrimination: a disparity may further reveal itself to be an instance of discrimination, but it may not. In America, 91% of nurses are female, a huge disparity. Is this disparity demonstrative of systemic sexism against men within health care? The demographics of “white collar” crime in America reveal that the majority of criminals are white men in their upper-thirties and forties, coming primarily from the middle class. Is the criminal justice system targeting this demographic? Younger (and disproportionate number of minority) drivers receive more speeding tickets than older drivers. Is this age (and ethnic) discrimination? Whites are underrepresented in the NBA but overrepresented in the NHL. Is this racism? The answer to all of these is not “Yes” or “No”; rather, it is: “Well, it might be, but it might not be. We would need to investigate further.” (I’d venture to say: too many progressives would be tempted to interpret any and all disparities as “evidence” of discrimination, while too many conservatives would be tempted simply to ignore the possible injustices that these disparities might indicate. Both are being presumptuous; and in so doing, neither is promoting the cause of racial justice.)

Far too many discussions of racism are, to say the least, difficult because at least one voice, though most likely most/all voices, are struggling, wittingly or not, under the crushing weight of the complexity of the topic. Unsurprisingly, the more simplistic and uninformed the participants, the more difficult and unfruitful the conversation is likely to be.

3. Significant culpability: Parking illegally is one thing; engaging in auto theft is another; and hitting a pedestrian while driving is still another. And when it comes to racism, the stakes are high. While there are worse things to be called than a “racist,” there aren’t many. When the topic of racism arises in a discussion, it’s not surprising that more than a few participants either assume a defensive posture or are eager to demonstrate to all that they are not (or are no longer) part of the problem.

4. Rising fears among faculty (and students) in higher education: Just last week Columbia University Linguistics Professor John McWhorter published an article in the Atlantic called “Academics are Really, Really Worried About Their Freedom.” Setting aside conservative perspectives on racism for the moment, McWhorter says that he regularly hears from progressive professors who fear that their views will no longer be regarded as progressive enough.

In their widely read book The Coddling of the American Mind, Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt describe this fear in detail. For example, when discussing the crucial difference between correlation and causation, they write, “Nowadays, when someone points to an outcome gap and makes the claim (implicitly or explicitly) that the gap itself is evidence of systemic injustice, social scientists often just nod along with everyone else in the room” (228).

And this past Sunday Robert George, a professor of jurisprudence at Princeton, tweeted, “I’m sorry that a climate of intolerance and fear is descending upon the academic world. I’m sad that many students and faculty are being subjected to subtle or blatant intimidation. It makes me unhappy to know that so many are afraid to dissent from campus ideological dogmas”–and he goes on to make an impassioned plea for academics to speak with the courage of their convictions, stating that it was an honor to make personal and vocational sacrifices in the name of truth.

It’s little wonder that everyday conversations about racism are difficult when those same conversations are found to be just as difficult, perhaps even impossible, in the one place where free speech is supposedly most hallowed: higher education.

5. The prioritization of feelings over facts: More and more today American culture, and Western cultures in general, are privileging the existential over the evidential: what we feel is most real. But while “lived experience” surely has its place as a kind of evidence and is a key ingredient for engendering empathy, it can be both highly deceptive and highly divisive: when persons on FaceBook disagree over an aspect of racism and both appeal to their own, or another’s, (typically very distinct) “lived experience,” whose experience is more authoritative and why? Should we listen first and foremost to the autobiographical reflections of a Ta-Nehisi Coates (a progressive) or a Jason Riley (a conservative), or perhaps a J. D. Vance?

All too often in discussions on racism, facts are sadly presented in a way that’s unfeeling, while feelings sadly carry the force of facts.

Accompanying this prioritization of feeling over fact is what has been called “the death of expertise” in America. In his book by the same name, Tom Nichols argues that, due to factors such as (1) the consumerization of higher education (in which the student–er, customer–is always right), (2) the internet’s limitless capacity to confirm all our biases, (3) the speed and spin of the 24-hour news cycle, and (4) the inaccuracy of too many experts (COVID-19 modeling, anybody?), Americans today are sadly too ready to disregard expert opinion. Not surprisingly, I’ve often seen experts cited in discussions about racism, only to be immediately–and unfairly–discounted.

6. Politicization: Although not new, matters of race and racism are increasingly being “weaponized” in political combat. If some conservatives have recently complained that progressives are inexplicably obsessed with racism, some progressives have interpreted the significant presence of minority voices at the recent Republican National Convention as using “blackness to sell a lie.”

How this makes everyday discussions of race more difficult is easy to see: participants are more readily influenced by their prior political preferences and allegiances.

7. Ideology: Right or wrong, good or bad, it’s no secret that the ideological foundations of the Civil Rights movement (as presented here) are significantly different from those that animate much contemporary discourse on race and racism, epitomized in the enormously influential organization Black Lives Matter.

Furthermore, while there has (very understandably) always been robust intellectual discussion and disagreement among leading voices within the black community (one thinks classically of Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois), over the past two (?) decades we have witnessed–and are continuing to witness–an impressive and multifaceted diversification (or fragmentation?) of intellectual convictions.

This diversification is far more nuanced than a simple “right vs. left.” To give a brief (and insufficient) example: Robin DiAngelo’s widely read White Fragility has been celebrated by some progressives but skewered by…other progressives.

While this diversification is undoubtedly a good thing, it further complicates discussions of racism, since all parties can (too?) easily cite, whether fairly or unfairly, their “favorite” minority scholar.

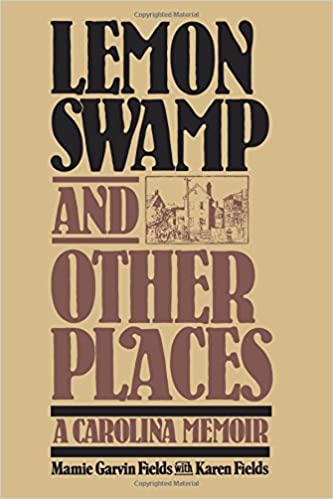

8. A heightened emphasis on “identity”: In a seminal collection of essays entitled Racecraft: The Soul of Inequality in American Life, written by Afro-American scholars (and sisters) Karen E. Fields and Barbara J. Fields, the latter recalls how she helped her grandmother write an absolutely wonderful memoir of her life in Charleston, SC, during Jim Crow. After describing the particular ways in which the racism of that time is illumined through her grandmother’s (a.k.a. “Gram’s”) memoir, Prof. Fields humbly and honestly alerts the reader of the following concerning “matters of race and color”:

“I acknowledge that these [matters] did not command Gram’s front-burner attention as they do mine. For her, they are there in the way Mount Kilimanjaro is there in Africa. For many intents and purposes, it is merely there, rising to its snow-capped peaks over the luxuriant tropicality of the town of Moshi. The mountain is hardly to be missed, yet hardly to be noticed, at once native and alien to the life around it. Tourists are the ones who preoccupy themselves with looking at it. I am saying this to give warning that, as Gram’s interlocutor, I was a tourist to her life with a tourist’s habit of gawking. Gram criticized me more than once for my preoccupation. She called me “angry.” Once she even called me ‘ugly’ on the subject and asked, ‘What must those people be doing to you up there?’ (‘Up there’ was Massachusetts at the time.) So I invite you to exercise methodological mistrust in my case, to be suspicious of the selections I have made in my own exercise of remembering. It is a fact that I cannot help gazing at Kilimanjaro” (185).

Earlier she states of her grandmother’s memoir, “Matters of race and color are a permanent presence without being her principal subject. They are constituent to life, but they do not define life” (184, emphasis mine).”

Regardless of how one chooses to interpret the differing perspectives of Professor Fields and her grandmother, one cannot deny the fact of their difference: while the racism of early/mid-20th-century Charleston was readily identifiable, race was not definitive for her grandmother’s identity. Today Professor Fields is in good company in her more profound (and probably unprecedented) awareness of racial identity in how she views both her grandmother’s world and her own.

The implications for discussing the topic are found in the very discussion–or disagreement?–that she and her grandmother had. Perhaps especially noteworthy is the latter’s suspicion of everything that her granddaughter was learning “up there” (at Harvard).

In addition to this heightened emphasis on identity, it’s certainly worth mentioning (and this could well be still another category) that ours is a highly individualistic culture: who I am is nothing more (or less) than the sum of my personal hopes, actions, achievements, etc. As such, it is a tall order to expect many Americans to see themselves as anything other than highly autonomous agents with little or no sense of a shared/inherited collective culpability or solidarity. While this may be especially true of persons belonging to the majority culture and/or color, it can also apply to members of minority groups as well.

9. Color, culture, class and creed: These–or at least the first–are what many readers would probably list first. It is perhaps most poignantly expressed by Du Bois (from which Coates presumably took the title of one of his books):

“Between me and the other world there is ever an unasked question: unasked by some through feelings of delicacy; by others through the difficulty of rightly framing it. All, nevertheless, flutter around it. They approach me in a half-hesitant sort of way, eye me curiously or compassionately, and then, instead of saying it directly, ‘How does it feel to be the problem?’ they say, ‘I know an excellent colored man in my town’; or, ‘I fought at Mechanicsville’; or, ‘Do not these Southern outrages make your blood boil?’ At these I smile, or am interested, or reduce the boiling to a simmer, as the occasion may require. To the real question, ‘How does it feel to be a problem?’ I answer seldom a word.

“And yet, being a problem is a strange experience,–peculiar even for one who has never been anything else, save perhaps in babyhood.” (The Souls of Black Folk, p. 15)

A major point of dispute–or at least discussion–would be the degree to which each of these four factors play a role in intensifying the difficulty of discussions of race and racism. For example, there is ample reason to think that especially class plays a far greater role than is often presumed: depending on their zip code, consensus views among 25-year-olds (irrespective of skin color) on all manner of things, to include race and racism, can be wildly different.

10. The news media and technology: The relentless blitzkrieg of the 24-hour news cycle, whether coming from the right or the left, chooses what, how, and how often to report on matters of race and racism, thus having an overwhelming influence in framing our everyday discussions. Based on the news media, how many Americans would believe what Harvard Law Professor Randall Kennedy observed over 20 years ago in his magisterial Race, Crime and the Law, stating programmatically, “An important theme of this book is that [throughout American history] blacks have suffered more from being left unprotected or under-protected by law enforcement authorities than from being mistreated as suspects or defendants, although it is allegations of the latter that now typically receive the most attention.”

When we add to this the technology of the ubiquitous smart phone, everyday discussions on racism gain access to “the scene of the crime” in a way that is unprecedented in its immediacy and ever so deceptive in its objectivity and simplicity, with politicians and the press often all too ready to weigh in.

To conclude, we shouldn’t overlook the contexts in which these everyday discussions take place: all too often it’s via social media. While these platforms have their upsides (e.g., one can step away and think about the discussion), they have their definite downsides, perhaps chief among which is that they can prove to be altogether dehumanizing.

How tragically ironic.

For any readers who would like a list of books to read on this topic, a list that is diverse both in ideology and genre, see my bibliography here.