As a young Jewish boy living in German-occupied Paris in the early 1940s, Nobel-prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman had a hair-raising encounter that, he later recalls, quite probably influenced his decision to study psychology.

He tells the story beautifully:

“It must have been late 1941 or early 1942. Jews were required to wear the Star of David and to obey a 6 p.m. curfew. I had gone to play with a Christian friend and had stayed too late. I turned my brown sweater inside out to walk the few blocks home. As I was walking down an empty street, I saw a German soldier approaching. He was wearing the black uniform that I had been told to fear more than others – the one worn by specially recruited SS soldiers. As I came closer to him, trying to walk fast, I noticed that he was looking at me intently. Then he beckoned me over, picked me up, and hugged me. I was terrified that he would notice the star inside my sweater. He was speaking to me with great emotion, in German. When he put me down, he opened his wallet, showed me a picture of a boy, and gave me some money. I went home more certain than ever that my mother was right: people were endlessly complicated and interesting.”

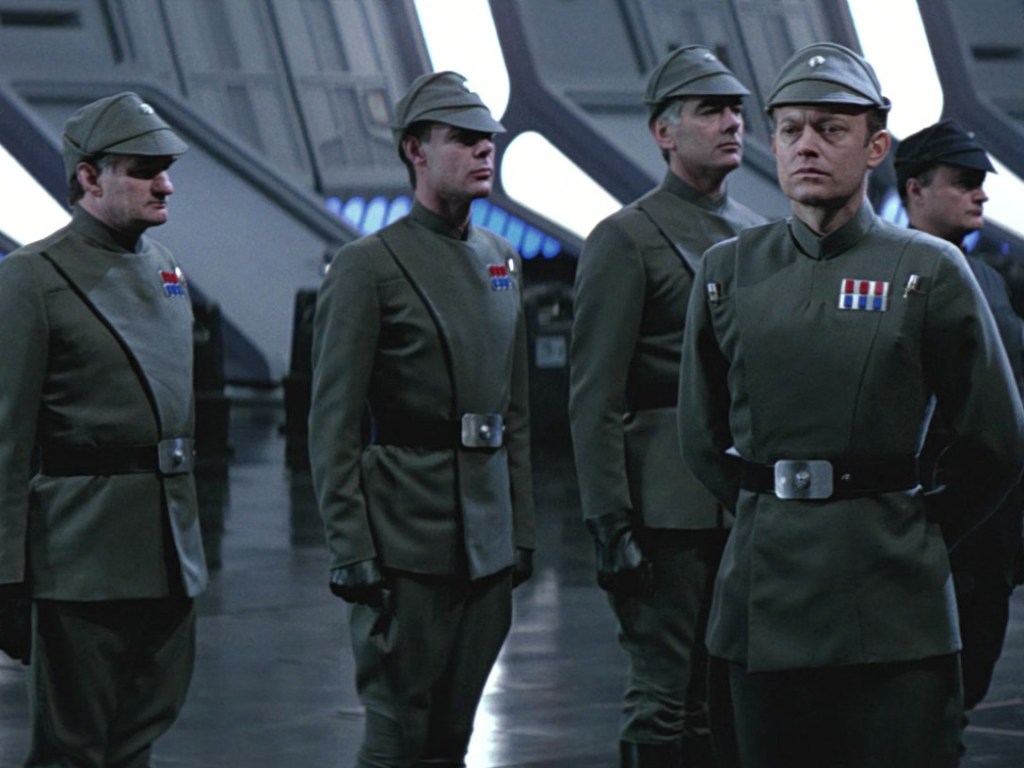

Who’s more villainous than a soldier of the Nazi SS (or Schutzstaffel), a paramilitary organization of Hitler devotees, whose powers of surveillance and savagery were as unmatched as they were unchecked? When filming the now legendary Star Wars trilogy in the 1970s, George Lucas intentionally designed the uniforms of the senior-ranking officers serving in the evil “Galactic Empire,” so as to look eerily similar to those worn by officers of the Third Reich.

And in the Star Wars films, whenever one of them dies, we’re all cheering–no reservations: after all, they’re villains, plain and simple.

Plain and simple. And that’s precisely what makes it Hollywood.

But, unlike Hollywood, Kahneman’s childhood story complicates our conclusions and problematizes our perceptions. With no little irony, this German SS soldier saw the 7-8 year-old son of Lithuanian Jews, and (presumably) a father’s heart was stirred with longing for his son back home, so much so that Kahneman became the actual recipient (or surrogate?) of deep paternal affection and generosity.

And, suddenly, this “simple” henchman of the Dark Side transforms into a human.

And such a transformative encounter can often serve as the key that opens the door to a whole new world of investigation and empathy: in fact, as the historical record shows, many German soldiers, up and down the ranks, despised Hitler and would have quite probably lived a catch-22 of competing values, agendas and allegiances–not least this particular soldier, who was presumably a husband and father: just what should resistance look like in such a situation?

Anyone immediately brimming with clarity on how to answer that one? (For the terrifying complexities of resistance, just watch the riveting Man in the High Castle.)

As with many children, the young Kahneman was a keen listener. He writes that often he would overhear his parents talking about various persons–family, neighbors, friends and foes. Concerning all these persons he observes ever so astutely, “Some people were better than others, but the best were far from perfect and no one was simply bad.”

Those who are “simply bad” exist, I would venture to guess, in only three places: first, in Hollywood; second, in online news hubs; and, third, in naïve human hearts.

We could say it this way: simply bad humans exist primarily in simple hearts.

Such simplicity is fertile soil for the vilification of…juuuust about anybody–be it a private person or a public servant, a prisoner or a police officer, a pastor or a parishioner (I think I’m guilty of pretty much all of the above). Further, vilification will thrive–whether in a person’s mind or in the news media whenever there are the following ingredients:

1. an ignorance of context: the details really can can be game-changing

2. an over-reliance on one’s own “lived experience” (or another’s–e.g., a smart phone video); after all, we’ve seen it all, right?

3. an uncritical reliance upon second- or third-hand information, whether it’s gossip (in interpersonal relationships) or an over-reliance upon non-attributable, “anonymous” or secondary sources (in journalism)

4. (and related to #3) an allergic reaction to actually interacting with the alleged villain themselves–that would be “too risky”

5. the conscious or unconscious disregard for deadly confirmation bias: we see only what we want to see

When these ingredients are present, vilification is very much a runaway train: all future information concerning the villain is interpreted through this framework, so that it serves as “evidence” that (1) confirms what has been “known all along” and (2) compounds the (supposed) pain experienced by the victim(s) in an exponential way. In some instances the “victim” even begins to associate all manner of misfortune to the apparently almost god-like influence of the “offender,” who may be a prior spouse (who has “ruined everything in my life”), a prior president, VP, or presiding president (who has “ruined everything in our country”).

Can the runaway train of vilification be stopped? Yes, by the most vilified person who ever lived, one who knew beforehand from sacred texts that his life would culminate in one grueling drama of vilification:

“He was despised and rejected by mankind…

like one from whom people hide their faces, he was despised…

we regarded him as punished by God, stricken by him…”

“But I am a worm and not a man, scorned by everyone, despised by all the people.

All who see me mock me; they hurl insults, shaking their heads.”

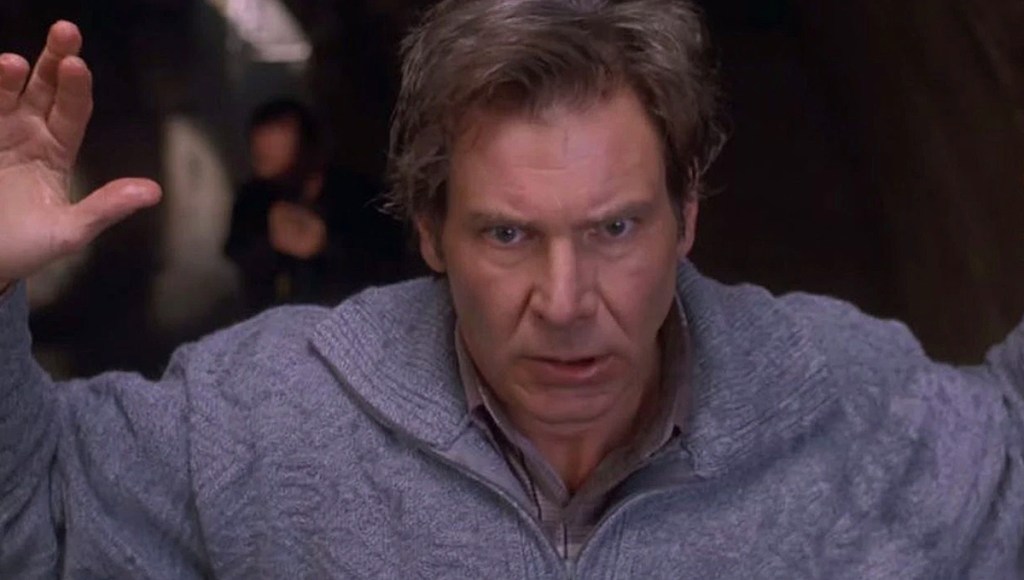

So would be the fate of the Vilified One, sent by a God whose most astonishing attribute may well be His nearly infinite forbearance of humanity’s (including the church’s and my own) relentless vilification of Him. Is not the 1993 Harrison Ford film The Fugitive an altogether fitting summary of the story of redemption, as a healer is falsely accused and imprisoned for murder, yet struggles to clear his name by exposing and overcoming the true agents of death?

But just as Jesus’ crucifixion reveals just how easily humanity can vilify even the most innocent and excellent among us, it provides an escape route from vilification.

Writing to some very polarized, partisan Christians at Corinth, Paul twice declares that through the blood of Christ on the cross, “You were bought at a price.” With this simple statement Paul shows how the cross reveals both the human dignity and human depravity that we all possess: Because of our great unworthiness (depravity), Christ had to purchase us with his blood. But because of our great worth (dignity), Christ was willing to purchase us with his blood.

In short, the cross of Christ speaks of both our great worth and our great unworthiness. But nowhere does it speak of our worthlessness, as though humans were simple villains.

Again, villains are found in Hollywood, in online news hubs, and in naive hearts. They’re never found in Holy Scripture: from Cain to Caiaphas, from Jezebel to Judas, from Pharaoh to the Pharisees, from the Canaanites to the Chaldeans, the Bible presents its “antagonists” as truly tragic figures; even as King David can cry out for God to visit justice on his malicious pursuers, when Saul actually dies, the warrior-poet laments, “O how the mighty have fallen!”; the prophet Ezekiel is told concerning the pagan kings of Tyre and Egypt to “Take up a lament”; and the wisdom literature explicitly warns:

“Do not gloat when your enemy falls; when they stumble, do not let your heart rejoice, or the LORD will see and disapprove and turn his wrath away from them.”

In marriage counseling I once asked a wife (with her husband absent) to list all the things that she admired about her husband. After 4-5 (very long, awkward) minutes, she could think of only three, and even these three weren’t exactly glowing. As a homework assignment, I asked her to take some more time to think about it and email me in a few days. She emailed three days later with one additional item.

This is vilification, and it’s disastrous. For everyone. Like racism, it’s both dehumanizing and divisive.

In this election season, I have asked my politically engaged conservative friends, “What policies or perspectives on the Biden/Harris ticket resonate with you?” And I’ve been asking my politically engaged progressive friends, “How do you think the Trump administration has helped the nation during his term in office?”

All too often my questions are met with silence, a silence that, more often than not, screams vilification.

The Biden/Harris platform wants to see the police funded in such a way that officers can park their patrol cars and walk through neighborhoods while on their beat. Does anyone think that this is not an incredibly good idea? The Trump administration has brokered peace agreements between Israel and not one but two Arab nations (the UAE and Bahrain), with more likely to follow. As far as geo-politics go, it’s a homerun. Shouldn’t we all be cheering?

None of this takes away from the fact we humans can commit truly terrible injustices, both as private persons and as partisan politicians. These injustices are not to be downplayed in any way. But if we really do conclude beyond a reasonable doubt that someone’s agenda is characterized by dehumanizing injustice, we must ourselves be all the more wary of doing the injustice of dehumanizing them by means of vilification.

After all, if they–whether it’s Trump, Biden or anybody else–really are our enemies, then we still have left to ask these two questions:

am I praying for my enemies, as our vilified Lord commanded?

and why am I not them?