In his own day MLK was regarded by many Afro-Americans as a man “sent from God,” even as “a modern-day Moses.”

Indeed, some regarded him as their “savior.” A certain Montgomery activist Rufus Lewis, who himself was not religious, observed that he couldn’t “see what’s the difference between him [MLK] and the Messiah. That’s just the truth about it.”

In short, he was a saint in his own time. And in our own time he’s still heralded as a hero, with his own holiday. But (unsurprisingly?) this saint was also a sinner. As breathtaking and bold as King’s spiritual calling may have been, sadly the spiritual cancer within his soul makes one wonder if he–and the rest of us?–should be “canceled” too. As one prominent historian of the Civil Rights movement says of King:

“The paper trail of [his] more serious moral failings… is now too conspicuous to be ignored.”

In the movie Selma what is discreetly hinted at in a poignant interaction between King and his wife is, sadly, undeniably clear–that King had numerous, ongoing extramarital relations. Indeed, if the recent revelations made by King’s renowned (Pulitzer-prizing winning) biographer David Garrow are true, then it seems that King’s extramarital liaison’s with other women, both single and married, were serial, even routine. Indeed, his sexual behavior may have been worse, transgressing into the non-consensual; I’ll leave it to the reader’s own investigation.

How should we think of King? How are we to reconcile a man who fearlessly championed the dignity of a deeply degraded 13% of Americans (Blacks) only himself to deeply degrade the dignity of 50% of Americans (Women)?

Should we–or, say, the #MeToo movement–demand that King be “canceled”–his holiday changed to something more generic, his Washington monument (and countless statues) torn down, and the buildings and streets bearing his name retitled?

But history’s “great men” are generally drowning in varying degrees of such tragic contradictions, no? One need only go from Martin Luther King to Martin Luther to see something not too dissimilar:

Just three years before his death (in 1546), Luther published “On the Jews and their Lies.” His vitriolic rantings, recommending violent action toward both Jews and their places (and implements) of worship, are stomach-turning. And this is the leader of the Protestant Reformation?

Or one could move from MLK to JFK and wonder not who Kennedy slept with, but who he didn’t sleep with. Portrayed to the public as the consummate family man, the historical record seems to show that Kennedy literally had no restraint whatsoever.

Moving from icons to institutions:

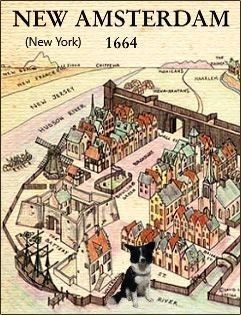

In a brilliant article in the Claremont Review of Books (“Cancel the New York Times“), Associate Professor of History at California State University (San Bernardino) Richard Samuelson wryly calls for the New York Times (and, by implication, New York City) to change its name. Why? As an historian, he reminds us that New York…

“…was named for James, Duke of York, brother of King Charles II of England…. [And] as the Daily Caller’s Thomas Phippen has noted in his discussion of New York’s name, James masterminded the newly created ‘Royal African Company’ that set out to take the African slave trade from the Dutch.”

So the New York Times is, indirectly, named after a slave trader. Isn’t that more than a little problematic?

(Samuelson’s article offers dispassionate historical reflections on–and corrections to–the NYT‘s “1619 Project.” His conclusions are the stuff of legitimate historiography–why?–because all too often his conclusions are–are you ready?–anti-climactic. For example: “So what actually happened in 1619? We don’t have enough evidence for there to be a definitive answer. Ditto how slavery grew in the British colonies.” Huh.)

Now let’s move from a city named after a racist duke to a party readily known by its donkey: the Democratic party. As Princeton professors Sergiu Klainerman and John Londgregan recently noted:

“In all this frenzy of name changes, one culprit is conspicuously missing. Up to the 1960s the Democratic Party was the party of slavery, Jim Crow, segregation, the Ku Klux Klan, lynching, poll taxes, and literacy tests for voting. The first Confederate Congress was dominated by former Democrats…. the Democratic Party dominated Southern politics, implementing a cruel regime of segregation in state after state of the former Confederacy. Nor were the Democrats in any great hurry to change their racist ways.”

In light of this, shouldn’t the Democratic party change its name, lest the significance of its mascot change from being a donkey to being… a jackass? (Or, wait, are those the same?)

(I should probably say: If from the above critique of the Democratic party, the reader infers a tacit endorsement of the Republican party, they would be assuming too much. But who can deny that most of the cries for “canceling” have come from those who would generally identify with…the Democratic party?)

Having covered a few icons and institutions, whom next should I eye? Along with the apostles, I’d like to (peacefully) protest, “Surely, not I.” But, duh, of course, I should cancel myself (maybe we could call it #iCancel?): what kinds of persons haven’t I marginalized, profiled, rendered invisible, objectified, manipulated, patronized, dismissed, degraded, assassinated in my heart, or pronounced “dead to me”?

From that irritatingly loud infant on the plane to the endlessly talking elderly woman, from the anally fit person to the “embarrassingly fat” person, from the “dude with the fro (or dreds)” to the immigrant with the impenatrable accent, from the redneck to the red turtleneck, not to mention most things French (except the food), journalists, realtors, “social justice warriors,” pastors with skinny jeans–these are all persons whom I met with premature, uncharitable judgments, all of which are explicitly condemned in Scripture, described with words like diakrino (διακρίνω) (“to discriminate”) and prosopolempsia (προσωπολημψία) (“partiality, favoritism”)–things that, Scripture repeatedly declares, God never, ever, ever does (Deut. 10.17; 1Sam. 16.7; 2Chr. 19.7; Acts 10.34; Rom. 2.11; Gal. 2.6; Eph. 6.9; Col. 3.25), but which I find myself doing effortlessly. (And this describes my participation merely in the interpersonal dimension of prejudice.)

Reader, there have been times I’ve contemplated suicide not just for what have done–the things I can never undo (and will do) but for who I am. I’d truly prefer my life mercifully forgotten, forever hidden in the sands of history.

But where does this all leave us? What in fact does all this canceling, name-calling and calling for name-changing really say? About them? About all of us? About you and me?

It says either of two things, the latter of which is overwhelmingly more likely.

First, the ascending “cancel” culture might possibly reveal that there really are “those people” out “there” who really do deserve to be “canceled” (shamed, fired, erased, etc.), and that they are fundamentally different from those who don’t deserve it. They are, to enter the world of Tolkien, like orcs, whose very constitution is a different metal from our own truly human (“woke”?) nature.

According to this perspective, life really is an “us vs. them.” If so, the supposed “untruth,” so widely propagated on college campuses today yet so effectively deconstructed in the book by Professors Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt, is actually true: “Life is a battle between [inherently] good people and [inherently] evil people.”

After all: we would never do that. I mean, Who. Does. That? How could “we” not be a superior breed?

This first perspective is made plausible whenever we make two very common yet highly questionable moves: (1) we quietly characterize moral failure in a largely externalistic, behavioral way, so that if I haven’t engaged in exactly the same behavior you have, it must mean I’m different/better than you; (2) we abandon critical self-reflection: why bother with the log in my own eye when there’s a speck in yours?

But Scripture–not to mention, experience–militates against this first perspective. For example, the Apostle Paul, in a truly amazing move, disregards the centuries-old ocean of differences between Jew and Gentile (differences that were ethnic, cultic, social, political, ethical, etc.) and declares that, at bottom…

“…there is no difference [between Jew and Gentile], for all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God.”

Paul’s strategy–found in the Old Testament and the Gospels–is simple: find a third party to critique (“those people”) and wait for his readers to agree with that critique, only to indict them as well:

“You, therefore, have no excuse, you who pass judgment on someone else, for at whatever point you judge another, you are condemning yourself, because you who pass judgment do the same things.”

Jesus voices a similar critique when he says, “With the measure you use, it will be measured to you.”

But Scripture’s common critique goes even deeper, arguing for a universal and inescapable complicity in human depravity. That is, the human problem isn’t just an all-inclusive hypocrisy, but an all-inclusive solidarity: here the (typically) progressive / liberal allegation of sharing in a larger multi-generational “white” systemic injustice actually doesn’t go far enough; we are all part of an even greater multi-generational “human” systemic injustice.

We see this played out in the Exodus story:

Undeniably, the enslaved Israelites find themselves trapped within a system of injustice explicitly defined along ethnic lines: in their affliction, they cry out to God, and he hears them, sending a deliverer. And yet, at the climax of God’s judgment upon Egypt, its king and its gods–viz., when God sends his death-angel to kill all of Egypt’s firstborn, we find that the enslaved, oppressed Israelites must themselves offer a sacrifice, lest their firstborn share in the fate of their Egyptian overlords.

How can that possibly be?

Apparently, for all their differences in “lived experience” and without in any way minimizing the very real differences in culpability, both Israelite and Egyptian, both slave and master, had even more in common. (Of course, as we go on to read in the Pentateuch, the Exodus generation tragically fails to enter the Promised Land–why?–because they proved to be no less “hard-hearted” and “stubborn” than the pharaoh [compare, e.g., Exod. 7.3 and Ps. 95.8].)

Without in any way dismissing the reality of specific injustices and inequities, Scripture finds all of humanity on the same team–the same wrong team. Those innocent of being an unfeeling, ferocious pharaoh lack not the depravity of a pharaoh but, more simply, the opportunity of a pharaoh.

If, as progressives seem prone to emphasize, poverty is a breeding ground for various pathologies, it seems that privilege can be as well. Huh. (Maybe privilege isn’t? More on that in a future post.)

But the universal “inclusivity” of Scripture’s damning accusation against humanity results in equally universal “inclusivity” of Scripture’s delivering invitation to humanity: just as Paul sweepingly, and scandalously, says that “all [Jews and Gentiles] have sinned,” he immediately (and no less scandalously) adds that “all” can be “justified freely by his grace through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus.”

In sum, unlike today’s “cancel culture,” Scripture indiscriminately cancels/condemns everyone to destruction. And also unlike it, Scripture indiscriminately calls everyone to deliverance.

Which, then, is the more inclusive? Ironically, the One most severe in his sentence is the most scandalous in his acceptance.

So how shall we then live? We should live by both mercy and mourning.

Whatever differences there may indeed be between master and slave, white and black, rich and poor, they are located not in any differing metals of our humanity but in the mysteries of heavenly mercy. “Where is boasting?” asks Paul. “It is excluded.”

And whatever differences there may indeed be are not to be mocked and made known to all (or even minimized) but rather mourned: like David lamenting Saul’s demise, let us grieve, “O how the mighty have fallen!” And unlike David, let us realize that our own demise may well come when the constraints of persecution and privation are gone, and we peer placidly from our palace roof of “privilege.”

For who among even the most devout of Jesus’ followers has not in their own way echoed the insistent words of Peter at the Last Supper:

“Even if I have to die with you, I will never disown you.” Then Mark notes:

“And all others said the same.”

So let us close, appropriately, with Augustine’s favorite verse, taken from Paul’s letter to the proud, divisive Corinthian Christians, where he challenges them:

“What do you have that you did not first receive [from God]? And if you did receive it, why do you boast as though you did not?”

Excellently written. Thanks for adding your thoughts to our world’s dilemma. Stay safe my friend.

Clear and irrefutable. What a blessing to be in the business of speaking truth into a world where anarchy, un-rule and untruth grab the headlines!

I needed to hear that, Bruce. Humbling and God-exalting.

I am really struck by this point that you make about the Hebrew slaves in Egypt–their status as victims of oppression didn’t exonerate them of their sinfulness before the holy God. I’ve been thinking a lot about how the Bible addresses the reality of specific injustices while it still “finds all of humanity on the same (wrong) team.” Looking forward to hearing your thoughts on privilege.

Yeah, this is illuminated in several ways: first, historically, while it doesn’t get much “air time” in the book of Exodus itself, it is implicit (and would’ve surely been already known by the original reader): by the time of the Exodus Egypt was in MANY ways been a glorious and truly magnificent civilization–and had been so for roughly two millennia!! Yes, indeed, the Israelites were slaves, but they hadn’t always been, and the complexities of power relations make it such that there would have been aspects of Egyptian life and culture in which the Israelites would have been both eager participants and true beneficiaries (not least since there was a time in Egypt when they had enjoyed significant status and freedom). My point: as participants and beneficiaries, they were in some sense complicit…in the same way that a North American evangelical Christan may be strongly critical of their culture’s institutions and structures and yet “benefit” tremendously from them.

Second, while the Israelites’ recollections of life in Egypt AFTER the Exodus (i.e., during their journey to Canaan and during the 40-year wondering) were surely skewed (“Wasn’t Egypt awesome? Let’s go back!”), at the same time there was a certain validity to those recollections, a validity which made those recollections so deceptive and dangerous: e.g,. from a dietary perspective, whereas they were now in a wilderness eating “the same darn manna” every day, back in Egypt they enjoyed the abundance fish of the Nile and quite probably some of the fruits of its rich agricultural produce. If interested, check out this post that speaks to the “benefits” of belonging to “the Empire”:

https://hopeunbroken.com/2015/04/27/disappointment-and-why-we-join-the-rebellion/

Joyfully,

btc

Well said. In considering the aspect of removing elements of our past history because of various transgressions do we not run the risk of it all being repeated? Would it be better to tell the whole story good and bad to keep all in front of us so as to help develop a fuller understanding and greater opportunity to work out the example Jesus demonstrated.

Those are really good questions, and I’m not sure I have good answers. Here’s my present take: the bible, both Old and New Testaments, seems to go out of its way to record the failings of its would-be protagonists: from Abraham to Moses to David to Nehemiah and, more generally for the nation as a whole (I mean, what are the prophets except a record of the nation’s repeated failings, but always with a promise of restoration?)–on every page of Scripture we see the artifacts of all manner of failure. We see a figure like David both in all his glory and in all his tragedy.

Even more intriguing is that we find in Scripture differing accounts of similar histories–classically, the history of Israel according to 1-2 Kings vs. that same history as recorded in 2 Chronicles. The latter, written later, actually leaves out a fair amount of the failures found in the first. It approaches the same history from a different perspective and with a different aim. The same could be said of the gospels, which have somewhat different perspectives on the disciples (with Mark being the most “cynical,” if you will). My point: it seems histories (or biographies) can be told from different angles, with different emphases and agendas.

I think what’s most challenging (for me) is this: when common/consensus recollections of a historical figure do in fact paint all too rosy (or all too ignoble) a portrait, what, if anything, is to be done? It seems that the record should probably be set straight in some way. That being said, when we discover that our heroes of the past actually had tragic flaws, it is a moment of crisis and reflection: how different from them are we, and, to the extent that we are, why? Should we be all too surprised when we come to find that–to use a very common, rather old line from English preaching:

Even the best of men are men at best

This was a thought-provoking read. Well-written. Thanks, Bruce, for the time you invested in thinking this through.